IT-enabled networks that capture all patient data and allow that information to be shared are the key to better, cheaper and more accessible care. But to realize their full potential, connected-health systems need the willing participation of all interested parties—policy makers, physicians and patients—in a carefully calibrated and collaborative enterprise.

Aging populations, rising rates of chronic disease,increasingly expensive treatments—the challenges of 21st century healthcare are staggering.The World Health Organization, for example, estimates that by 2015, chronic diseases will account for 64 percent of all deaths—a 17 percent increase since 2005.

Public officials worldwide are seeking ways to meet these challenges, trying to deliver improved outcomes at lower costs. Connected-health systems—IT-enabled networks that capture all patient data and allow it to be shared are widely seen as the key to better, cheaper and more accessible care.

Indeed, R AND Health reckons that interoperable electronic medical records could cut between $142 billion and $370 billion from the projected 2018 US healthcare bill of $4 trillion.

AND Health reckons that interoperable electronic medical records could cut between $142 billion and $370 billion from the projected 2018 US healthcare bill of $4 trillion.

Denmark, a world leader in the adoption of healthcare IT, is among the 10 nations, regions and healthcare systems that our research has identified as exemplars of current best practices in connected health (see sidebar, page 7). In the 1990s, the country first established a national digital data network for health that is now used by all hospitals and pharmacies, as well as a majority of its primary-care physicians. Citizens can also access the network via the national e-health portal.

Coupled with mobile health initiatives that enable doctors to manage patients with chronic conditions remotely, usually in their own homes, this digital data exchange has helped the Danes manage health costs better and enhance their health services significantly. It has contributed, for example, to a dramatic reduction in the length of hospital stays—to less than half the European average, in some instances.

Technology, however, is only part of the answer when it comes to delivering higher-quality, more cost-effective and accessible healthcare. What really distinguishes Denmark’s system is its governance—especially the degree of cooperation between the system’s multiple stakeholders. Government directives encourage compliance with overall goals and standards but are otherwise strikingly non-prescriptive. Professionals (and patients) within the country’s five administrative regions, along with 98 local authorities, are free to come up with their own solutions, which can become nationwide models if they improve clinical or administrative processes.

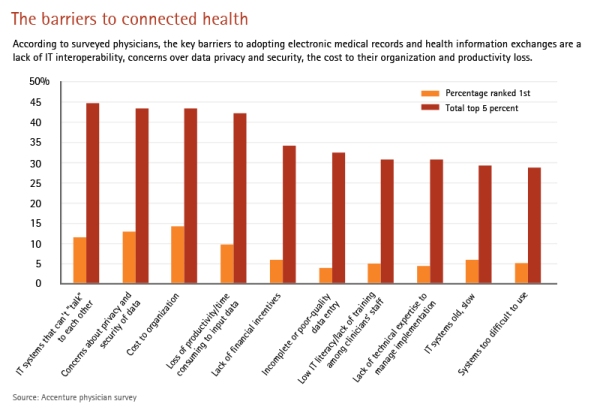

The barriers to connected health

According to surveyed physicians, the key barriers to adopting electronic medical records and health information exchanges are a lack of IT interoperability, concerns over data privacy and security, the cost to their organization and productivity loss.

As Accenture discovered when we set out to track progress toward connected health across eight core countries (Australia,Canada, England, France, Germany, Singapore, Spain and the United States), the ability to use technology to exchange data—between clinicians, across administrative groups and with patients—does deliver value in terms of reduced administrative costs, enhanced clinical decision making and new capabilities for preventative care.

But a flexible, inclusive and collaborative governance structure to manage information exchange is the real key to achieving true connectivity across the entire continuum of care.

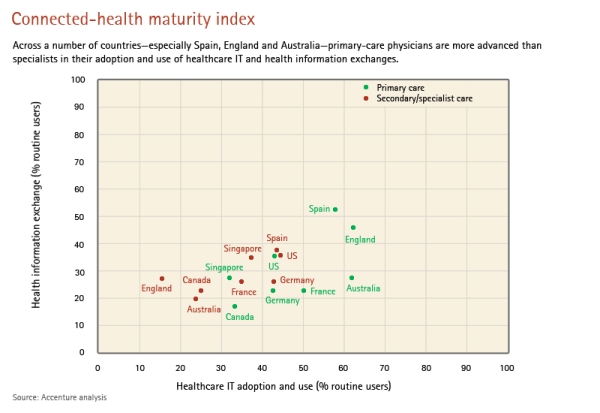

Our research revealed a dramatic variation in progress toward connected health among the eight countries that were the focus of our investigation. Some are moving steadily toward systems that can share health information nationally, particularly in primary care. In Spain, for instance, where roughly 90 percent of patients now have their healthcare data stored electronically, most regions have well-functioning electronic health record systems. And the government has launched a national digital health initiative, which is working toward nationwide connectivity.

Skeptics

The approach of other countries, however, remains remarkably fragmented. Healthcare IT adoption in Australia varies significantly across care settings, states and territories. In France,large urban areas are moving more quickly than rural regions.And in Germany, healthcare IT is used in both primary and secondary-care settings for administrative processes but has yet to catch on among clinicians.

Skepticism among physicians can be a major obstacle to healthcare IT adoption. Few countries are quite like Denmark,where tech-savvy doctors are widely admired as trailblazers.

Moreover, the Danes, who have had a national ID register in place since 1968, plainly trust their government to keep personal data safe, which is not the case in many other jurisdictions.

Indeed, concerns about privacy and data security ranked high when we asked doctors across the eight countries to name the top five barriers to healthcare IT adoption. Yet cost, in terms of both time and money, was an equally significant concern—suggesting that with the right mix of cash incentives and managerial reassurance, misgivings about healthcare IT can be overcome.

In Italy, for example, doctors and pharmacists in Lombardy (another of our 10 best-practice examples) were paid to enter data into the region’s digital health information exchange and actively promote it with patients. In France, meanwhile, citizens’ concerns about data security and privacy were tackledhead-on—by engaging them directly in the design of a connected system. ASIP Santé, the central agency that oversees and steers the nation’s e-health implementation, has worked with the public to improve a much-criticized single electronic health record model, held on a central server. French citizens can now choose which provider holds their main record, and the central database contains only demographic information and indexes that direct users to local systems where more detailed data is held.

Connected-health maturity index

Across a number of countries—especially Spain, England and Australia—primary-care physicians are more advanced than specialists in their adoption and use of healthcare IT and health information exchanges.

Regardless of where they are on the path to healthcare IT adoption and the integrated healthcare delivery it heralds, our research shows that all players will build more solid foundations if they can master best practice within six interrelated areas.

1. Vision and leadership focused on improved health outcomes

The leaders in creating connectedhealth systems set objectives that reflect a clearly articulated vision of healthcare of the future. In Singapore, for instance, authorities have been exemplary in creating and communicating such a vision—“one Singaporean, one health record”—and in making a strong business case for its benefits. Canada, via Canada.

Health Infoway, an independent central body coordinated by the ministers of health of the country’s 13 provinces and territories, has developed “2015: Advancing Canada’s Next Generation of Healthcare”—a detailed digital blueprint for enhancing patient communication and access.

Such initiatives enjoy the full support of governmental leadership and are top national priorities. Singapore’s program,for instance, is part of a wider master plan to transform key areas of government through IT. And because sustaining top-level commitment can be tricky in an industry as politicized as health, these experiences underscore that continuity of leadership, strategy and message are critical success factors.

2. Strategic change management

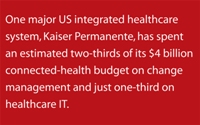

One major US integrated healthcare system, Kaiser Permanente, has spent an estimated two-thirds of its $4 billion connected-health budget on change management and just one-third on healthcare IT. Our research suggests that such ratios are common among those who succeed.

Connected-health leaders work particularly hard to engage doctors early in the process—and they constantly review the effectiveness of their communications and programs. Kaiser,for instance, arranged coaching for physicians struggling to master the use of electronic health records. And Singapore officials, by working closely with physicians to develop the country’s Electronic Health Record, have come up with a design that doctors find relevant to their routine practice.Moreover, by piloting processes, demonstrating benefits and being willing to change systems and protocols in response to feedback from physicians on their frontline needs, the authorities have built wider support.

Our research did find that populations or subscriber numbers in excess of 10 million may be just too big to handle successfully through a single connectedhealth network.

Singapore’s health system serves just 5 million people, for example—a clear advantage.

But that doesn’t mean larger jurisdictions are doomed to failure—far from it. Generating responsibility and momentum at the local level drives progress on the national journey. Consider, for example, US federal government efforts to create regional connected-health hubs, bound together by common standards,certification processes and incentives, to form the Nationwide Health Information Network. A federally appointed national coordinator for healthcare IT is setting strategy and goals for connected health, as part of federal legislation designed to encourage the use of both electronic health records and health information exchanges.

3. Robust technology infrastructure

A standards-based and scalable IT architecture is a fundamental building block of connected health. But it must align with the health system’s overarching vision, and be able to adapt as the needs and aspirations of citizens, clinicians and health managers change.

That’s a tall—and potentially costly— order, especially given the fast pace of technological change, which can render leading-edge components obsolete virtually overnight. But the leaders know that technology is not a one-time cost. They also know that modular strategies—a phased approach— are the way to ensure that IT architectures can adapt and evolve, limiting risk, and that technology systems can be implemented at a rate that allows change management processes and strategies to keep pace if common standards and procedures are in place. Common standards, indeed, are the basis of stable and secure information governance—the key to winning physicians’ support for connected health.

Hong Kong offers an outstanding example of how a strong foundation can be built around such standards and procedures,even when resources are squeezed. The healthcare authorities began by building simple clinical support modules, such as patient discharge summaries, around existing technology—and gradually added appointment booking, laboratory, radiology and referral modules.

Crucially, they worked hand in glove with physicians, who guided the development of this clinical management system,which now provides core, integrated healthcare IT capacity across 41 public hospitals and 122 outpatient and specialist clinics, and which played a key role in tracking the spread of the SARS outbreak in 2003.

4. Co-evolution

Co-evolution is about striking the right balance between strong leadership from the top and innovation on the front line.Successful connected health requires both. Local needs drive site-level innovations, and then leadership takes the lessons and disseminates best practices across the system to build interoperable connectivity.

In a few countries—notably Denmark, where the national healthcare data network actually began as a regional initiative—collaboration between healthcare professionals and the policy community is a well-established tradition. But other nations have been similarly receptive to local clinical innovations—and have reaped similar rewards.

In Scotland, for example, a consultant physician and research director took the lead in developing a web-based clinical information system for diabetes care in the Tayside region. The successful pilot became an award-winning, nationally integrated single-patient record for diabetes that spans primary, secondary and tertiary care for 239,000 sufferers.

Moreover, the experience has persuaded the Scottish eHealth Programme to commission more local connected-health projects, which, if successful, will be rolled out across the country.

5. Clinical change management

Clinical change management involves optimizing the efficiency of clinical service provision, and requires the skilled use of sophisticated analytics to improve diagnostic capabilities—which does not come cheap. Moreover, realizing the improvements that analytics can identify hinges on exceptionally strong clinical governance— regular physician peer review, performance management and agreedupon procedures for the design and implementation of new clinical protocols.

Physicians often need persuading that the return on investment for their precious time justifies the cost of maintaining such systems. But the experience of Intermountain Healthcare, a nonprofit, integrated healthcare system based in Salt Lake City, Utah, is compelling.

Intermountain leverages systemwide electronic health records containing 30 years’ worth of data to develop standardized protocols for improving care for the 10 percent of conditions that account for 90 percent of the services its patients use. The 3,200 doctors within the system’s network lead the task forces that design and implement these protocols. And their efforts have already resulted in significantly better healthcare for the 3.6 million people they serve.

Among Intermountain’s successes:

A 50 percent improvement in the proportion of cardiac patients receiving appropriate medication, a 40 percent decline in pneumonia mortality rates and, thanks to more extensive screening procedures, a significant decline in the number of babies born in Intermountain Healthcare’s hospitals that develop jaundice.

6. Integration drives integration

The best connected-health systems are mutually reinforcing. Effective strategic change management, for example, supports changes in clinical practice—and the two dynamics maximize their power to enhance patient care by operating in tandem.Such effects are accelerated as more information and clinical practices are shared across teams, organizations and systems:

More integrated healthcare IT drives more integrated healthcare delivery, which in turn drives further integration of IT.

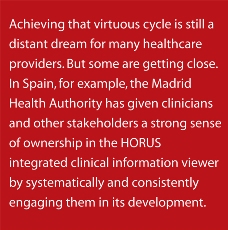

Achieving that virtuous cycle is still a distant dream for many healthcare providers. But some are getting close. In Spain, for example, the Madrid Health Authority has given clinicians and other stakeholders a strong sense of ownership in the HORUS integrated clinical information viewer by systematically and consistently engaging them in its development. HORUS is now driving the digitization of paper hospital records. And as clinicians in both the city and region of Madrid continue to use,evaluate and benefit from the integrated functionality that HORUS already delivers, connectivity will be further enhanced.

Connected health is an evolutionary journey. It begins with a clear vision and requires inspiring leadership to empower and shepherd the process. And a robust technology infrastructure is fundamental to its success.

But our research also reveals the critical importance of co-evolution and collaborative change management, involving all stakeholders,especially physicians, and enabled by analytics to help create better ways of solving clinical challenges on the front line. For citizens,meanwhile, the increased availability of remote care will offer new and more cost-effective ways for patients to co-manage their own health (see sidebar, page 6). And as health authorities become better at measuring progress, identifying benefits and achieving connectivity between primary- and secondary-care settings,integrated healthcare delivery will become a reality.

No country has yet achieved the ultimate goal of the connected-health journey—an insight-driven system of care with patients at its core and where advanced data analysis sustains innovative delivery models both within and across populations. A few, however, are well on their way.