The underlying principle behind the inability of any health system to offer all medical services, to everyone, right now and all the time, has to do with the fundamental driver of all economic activity: resource scarcity. Ultimately, resources are scarce and economic and ethical decisions must be made by any society as to how these resources will be allocated.

Currently no health system attempts to attain all four offers at the same time, but when you reflect on it, only the goal of providing care for everyone is realistic (1).

At a regional level in Asia, the gap in the quality of delivered care and healthcare system’s performance between countries remains as wide as the Pacific Ocean. The differences in Healthcare systems’ maturity levels are dictated mainly by the economic stability, political leadership and common health and demographic indicators.

However, despite all these and other major challenges, today many advanced countries have an unprecedented opportunity to create a high-performance health system by leveraging newly implemented tools. The challenge though is to find a way to empower providers and patients to rapidly improve the care they offer and receive. Though there is no battle-tested plan for doing so, a logical approach would emphasize three tools and one overall policy strategy. The tools are improved primary care, payment reform, and better information (4).

Moreover, the relationship between patients and doctors is changing, but is still at the core of medical ethics, serving as an anchor for many of the most important debates in the field. Over the past several decades, this relationship has evolved along two interrelated axes — as it is defined in clinical care and society. (2)

CLINICAL CARE

Until the 1960s, most codes of medical ethics relied heavily on the Hippocratic tradition, framing the obligations of physicians solely in terms of promoting the welfare of the patient, while remaining silent about patients’ rights. The past several decades have seen tectonic societal shifts that have resulted in increasing empowerment of inpiduals against the authority of government and institutions, creating a surge of rights-based movements, with patients’ rights emerging as a societal demand alongside women’s rights, minority groups’ rights, consumers’ rights, and others. (2)

This dramatic shift appeared to move the locus of authority in decision-making from the physician to the patient. And indeed the emergence of the Internet, has given many patients the impression that they can largely manage their own medical affairs, with physicians serving primarily as consultants. But the reality is more complex: the wealth of information available to patients has proved to be as dangerous as it is helpful, and today patients and physicians are beginning to find a healthier balance of power through a process of shared decision making. With this approach, physicians are seen as having expertise and authority over matters of medical science, whereas patients hold sway over questions of values or preferences.(2)

Particularly in Asia, this approach has many implications — for example, in recognizing the right of a competent adult to refuse a lifesaving blood transfusion on the basis of his or her religious beliefs, or the right of a patient to refuse mechanical ventilation for a treatable and reversible cause of respiratory failure. At a system level, this has led some major US healthcare organizations to change the way care is delivered today:

The largest U.S. health insurer, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), has set a triple aim: better care for inpiduals, better health for populations, and lower costs. Simultaneously, major efforts have been launched to make care more patient-centered, defined as “respectful of and responsive to inpidual patient preferences, needs, and values, and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions.” Attention to patient-centered measures and outcomes will be particularly important as CMS moves increasingly to link health care providers’ reimbursement to their performance on selected measures.

In Australia, national and state governments signed the National Healthcare Agreement in 2008. The latter outlines the goals of the health system and specifies roles and responsibilities of these governments in managing and providing health services. Signatories to the National Healthcare Agreement are accountable to the community for their progress against the agreed outcomes of the agreement. The agreement contains a set of progress and output measures to support assessment of progress towards the agreed outcomes. Unfortunately, assessments of quality of care and health outcomes have not yet incorporated patient-centeredness. Rather, measurement of quality has addressed preventive and disease-specific care processes (e.g., elective surgery waiting times, emergency departments’ performance). Similarly, outcomes measurement has focused on condition-specific indicators, both short-term (e.g., hypertension control) and longer-term (e.g., smoking cessation), as well as overall mortality.

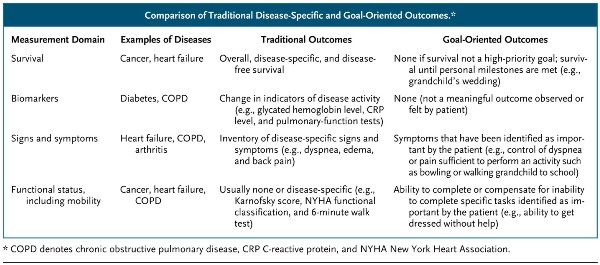

Though these process and outcome measures work well for relatively healthy patients with single diseases, they may be inappropriate for patients with multiple conditions, severe disability, or short life expectancy. For such patients, the overall quality of care depends on more than just disease-specific care processes. Furthermore, disease-specific outcomes may not adequately reflect treatment effects in patients with multiple coexisting diseases (3).

An alternative approach to providing better care would be to focus on a patient’s inpidual health goals within or across a variety of dimensions (e.g., symptoms; physical functional status, including mobility; and social and role functions) and determine how well these goals are being met (see table).

For example, a person with Parkinson’s disease may establish goals for symptoms, such as decreased rigidity and no falls; goals for functional status, such as the ability to get to the bathroom without assistance although requiring a walker; and goals for social function, such as the ability to use the Internet to communicate with a grandson at college and the ability to go to church. However, the patient may not be aiming to reduce tremor, walk without a walker, or continue to work for pay. Alternatively, he or she may prioritize being as mobile as possible even at the expense of medication-induced dyskinesia and mild confusion. (3)But perhaps the most important barrier to goal-oriented care is that medicine is deeply rooted in a disease-outcome–based paradigm. Rather than asking what patients want, the culture has valued managing each disease as well as possible according to guidelines and population goals. In China, the opportunity to merge the forces of modern and traditional Chinese medicine towards a goal-oriented care is very appealing, but the isolation of both practices from each other is less encouraging to drive such an initiative.

POPULATIONS AND HEALTH CARE SYSTEMS

The United States already spends more on healthcare than any other country on earth yet does not attain the health benefits that are achieved in many countries with much more limited resources. Singapore has a known shortage of nurses, spends less than half of the percentage points of US-GDP on healthcare and has significantly better health indicators and outcomes than the US. Despite the seductive view that the relationship between physicians and patients should be isolated from any external pressures, we must recognize that population-based factors such as justice, efficiency, and fairness are also ethically relevant (2).

Nothing is more important for improving performance in caring for patients with complex conditions than coordinating care and enhancing access during normal office hours, nights, and weekends — precisely the role that good primary care plays in high-performing health systems. Payment reform is essential to enabling providers, and perhaps patients, to participate in the savings that result from reductions in costs and improvements in quality. And care coordination and cost management depend on having accurate, timely, and actionable information in real time at the point of decision-making. The availability and effective use of health information technology are therefore essential to improving health system performance for high-cost patients (4). Recently, both Singapore and Australia embarked on a journey of harmonizing and digitizing their citizens’ health records at national levels. Beyond directly contributing to a more accurate care delivery, the gradual and meaningful adoption of such information systems represents a priceless resource for population health and disease prevention.

CONCLUSION

The reality is that every society makes choices about their health system and the inevitable compromises that must be made. But beyond political sways and in order to help overcome the healthcare resource scarcity issues while delivering superior outcomes, integrated healthcare organizations should be looking at 2 more levels of action:

1. A guided and pragmatic participation of the patient in the decision-making process, especially for patients with multiple conditions.

2. A diligent and thorough education of target populations on wellbeing and the risks of specific disease burdens.

Finally, the execution of such an endeavor requires setting the right framework of actions and having the rights leaders in place. This framework will actions all the levers of communication, support informed decision-making and objectively measure its impact at the inpidual, healthcare organization and population levels.

In developing a sustainable capacity to endure uncertainty, healthcare providers and their patients are embarking on a journey towards a higher-performing care delivery mechanism with a myriad of benefits for all stakeholders. In high-paced Asia, the decade to come will be a very interesting one to follow.

Mehdi Khaled: the views expressed here are my own.

References:

1. Health Economics 101

2. Robert D. Truog. Patients and Doctors — The Evolution of a Relationship. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:581-585

3. Reuben DB, Tinetti ME. Goal-Oriented Patient Care — An Alternative Health Outcomes Paradigm. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:777-779

4. Blumenthal D. Performance Improvement in Health Care — Seizing the Moment. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:1953-1955